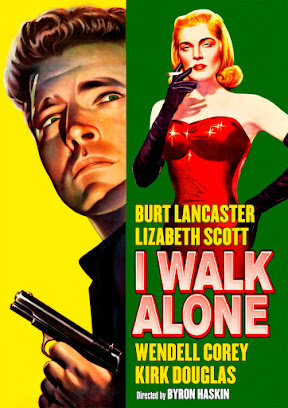

ONCE I TRUSTED A DAME... NOW I WALK ALONE!

Fourteen years ago, Frankie Madison (Burt Lancaster) and Noll ‘Dink’ Turner (Kirk Douglas) were small time bootleggers making a reasonable living running whiskey to supply their little speakeasy bar. But, when one fateful run goes bad, the two split up over a handshake promise to get the other a good lawyer and a guaranteed 50% stake in their business if one of them gets caught & sent up the river.

Now it’s 1942 and prohibition has been over for nine years. Frankie's released from prison and goes looking for the 50% cut of his 14 years of accrued profits, plus interest. But times have changed. Dink has parlayed the speakeasy into a respectable, high class joint, The Regent Club, which he has no intention of splitting with his old partner. Frankie’s Age of Bootleggers & Gangsters has now been replaced by a slick, post-war Brave New World where illegal activities don't use Tommy guns, just a fountain pen entry in a ledger book. Can Frankie’s old school strong arm tactics be enough to trump Dink’s savvy brand of legalized corrupt capitalism?

A showdown is coming and the only wild

card in the scenario is, of course, a dame – Kay Lawrence (Lizabeth Scott).

I Walk Alone (1947) is based on the play The Beggars Are Coming

to Town by Theodore Reeves, with a an adaption by Robert Smith (99 River Street,

1953) & John Bright (The Public Enemy, 1931), and a screenplay by Charles

Schnee (Red River (1948) and The Bad and the Beautiful (1952)). The ‘I’ in the

title seems to be directly referring to the nation of disoriented WWII veterans

who had fought a war where the strength of their hands and spirit, derived from

generations of rugged pioneer life, was enough the win the Big Prize. But, like

Frankie, they’ve came home to find their former reality erased and replaced by

a capitalist system based not on success by hard work, but rather by manipulating

the rules and red tape that can conceal and legitimize any criminal activity.

When Frankie pulls together a new gang to force Dink into giving him what he believes he deserves, the film shifts into what amounts to a cold-hearted lecture aimed squarely at the ex-servicemen in the audience about how the new post-war America actually works. The always boring to watch Wendell Cory channels his own bland personality playing Dink’s accountant, Dave, as he dryly explains the tangled shell game of dummy corporations that leaves Dink in charge of his operation, but only owning a small percentage of it. Frankie’s gang slowly realizes that there is nothing to muscle in on and drifts away – how do you threaten a bunch of intangible laws and regulations? They even apologize to Dink on their way out, probably hopeful for future work with his winning side.

Can Frankie rally his now outdated skills to beat Dink at

a game he doesn’t really understand? Fortunately he has two things on his side –

the love of Kay who’s just been dumped by Dink as he sleeps his way up the

social register, and the finally pushed-too-far Dave, whose illegal second set

of ledgers for The Regent Club could end Dink’s high life career.

In the fateful final showdown, it boils all down to this statement by Frankie to Dink,

“When it comes to stocks and papers, and books that don’t balance, you’re better than me. But, when it comes to guns, you’re down on my level.”

The last act of the film shifts into high gear after the steady build up of its first two-thirds, making the audience hold on through multiple sharp turns that will leave them guessing (well, maybe not too hard) as to the final resolution.

Three main stars of the film – Burt, Kirk and Lizabeth – were only one or two years into their careers at this point, but they already had the charisma and acting chops would carry them on to their varying degrees of stardom.

Burt Lancaster plays Frankie as a man uncomplicated by any

deep understanding of his world – does a fish even notice the water it's

swimming in? Some reviewers have criticized Lancaster’s two note performance –

dumbfounded or rageful – as lacking depth, but I don’t see any other way that

the character could have been portrayed. What Frankie wants he takes by the

strength of his hands and a willingness to take big risks – easy to do when you

have nothing to lose. Lancaster would specialize in characters who didn't like to be pushed around.

Kirk Douglas was establishing himself as an actor who

could smoothly inhabit any cool & ruthless crime boss who always has an angle to

play. Douglas’s role as Noll (always 'Dink' to Frankie, but nobody else) is

just a slightly different take on the part that he had just played opposite Robert

Mitchum and Jane Greer in Out of the Past (1947). Aspects of this character

would be a hallmark of the rest of Kirk’s career.

Lizabeth Scott’s unusual beauty and husky voice made her

a natural for the film noirs that she would become noted for. Groomed as a

Lauren Bacall clone, she and Bacall had one defining difference that would

always separate the two. No matter how down on her luck Bacall’s character may

have been, she could never help but radiate sophistication and class. In

contrast, Scott was always a ‘dame’ – and we loved her for it. Always on the wrong

end of bad deal, you knew that no matter how hard Scott tried, she was always

going to end up unhappy (e.g., Pitfall, 1948).

I always enjoy watching the supporting actors with small parts in these old films. Among the notables here is fan favourite, Mike Mazurki (Dan) (above), one time member of the Frankie-Dink Gang, now holding down a job as Dink’s Doorman/Bouncer/Muscle. Mazurki was sort of the Dwayne Johnson of his day. A former wrestler, the 6’5” Mazurki was a busy actor almost always playing a beetle-browed heavy. He was likely hired for this part because he would have been the only actor in Hollywood who could have been believable in taking Burt Lancaster out with one punch. Also watch out for Former World Middleweight Boxing Champion, Freddie Steele, as a member of Frankie’s short lived gang. He may be best remembered for starring alongside Robert Mitchum in The Story of G.I. Joe (1945).

The number one reason to watch this film is for the storytelling skills of director Byron Haskin. Every shot is perfectly composed and lit for maximum noir-like effect. Normally I’d credit this to the cinematographer – Leo Tover, the highly regarded lensman behind a number of terrific films from the 40’s & 50’s – but Haskin’s strong hand makes what is frankly an average, oft told story, compelling. Every scene is a master class in how to have your characters interact for maximum audience engagement, even when the dialogue seems more theatrical than real.

Haskin’s early career began with him directing in the 20’s before becoming a cameraman and special effects expert. From 1937 to 1945, he headed up the Special Effects Dept. for Warner Bros, earning four Academy Award nominations. I Walk Alone was his first credited directorial role in the talkie era, a career that lasted into the late 60’s. He was a frequent collaborator with producer, George Pal (e.g., directing War of The Worlds, 1953), and is responsible for directing arguably the two best Science Fiction stories ever filmed, The Outer Limits episodes Architects of Fear (1963) and Demon With A Glass Hand (1964).

Is I Walk Alone Worth My Time? Definitely. While not a true Noir (as I would interpret the genre), it pulls no punches in its depiction of ruthlessness and treachery that end up getting their requisite karmic sting in the end. At 97 minutes, it’s a nicely streamlined, if not original story, featuring three great actors at the dawn of their careers and peak of their beauty.

Availability: I Walk Alone (1947) finally got a nicely cleaned up DVD release from Warner Archives in 2018, having gone missing since being in heavy rotation on television in the 60’s and 70’s.