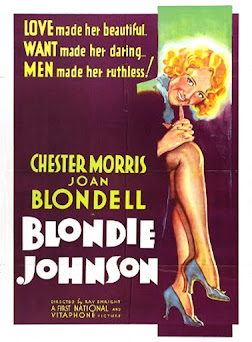

GOOD GIRLS GO TO PARIS (1939) is a Columbia Pictures romantic comedy directed by Alexander Hall and starring Joan Blondell, Melvyn Douglas and Walter Connolly.

Jenny Swanson (Blondell) plays a good-hearted waitress who thinks that she is not above a little harmless gold digging blackmail to fulfill her dream of going to Paris. All that changes when she meets the Aesop-quoting, English exchange professor, Prof. Ronald (‘Ronnie’) Brooke, (Douglas) who sets her conscious – and heart – aflutter.

Jenny is working at the diner near the local college as she tries to snag herself a rich student, extract a promise of marriage from him, and then collect a big payoff from his father when he objects to the marriage. When Jenny strikes up a friendship with Douglas’s professor and tells him of her plan, he advises her that "good girls go to Paris, too" and that she should go straight back home to Minnesota. When her blackmail plan seemingly blows up in her face, she heads for the train station, but in a last minute decision buys a ticket for New York City.

On the train she hooks up with the Tom Brand (Alan Curtis), brother of Brooke’s previously unmentioned fiancée, Sylvia (Joan Perry), and soon ends up as the inadvertent house guest of the wealthy Brand family.

All of the family have their secrets. Brooke’s fiancée, Sylvia, is really in love with medical student Dennis Jeffers (Henry Hunter), the son of the Brand’s butler. Mother Caroline (Isabel Jeans) has a not-so-secret paramour, Paul Kingston (Alexander D’Arcy), and Tom has a $5000 gambling debt hanging over his head. All of their problems stem from their inability to stand up to their overwrought, overbearing and continuously apoplectic patriarch, Olaf (Connolly).

Can our little Jenny untangle everyone’s problems and ensure that everyone – including her and the professor – all end up with the right partners?

The ending might not be a surprize, but the path that Jenny takes to get there, constantly guided by her inner ‘flutter’, is a continuously unfolding delight. Jenny’s every interaction adds a new complication that she has to solve by hook or by crook – happily using the latter when she gets cornered into doing a little well-meaning blackmail to save Tom’s hide from the gangster he owes money to.

By the end of the film every male has proposed marriage to Jenny at least once - all except, of course, for Prof. Brooke!

If you wanted to call this a screwball rom-com, I would not argue with you. The cascading series of comedic crises that drag Blondell’s character into the Brand family’s orbit, and the sparks they generate, are the hallmarks of a good screwball. But every really good screwball comedy needs a solid cast of memorable (and often eccentric) supporting characters. Blondell, Douglas and Connolly all have terrific screen presence and know how to get the most out of an almost A-quality script, but the rest of the cast are so bland as to be interchangeable. While writing this review I had to consult the IMDB a dozen times to keep these characters straight. Is Isabel Jeans playing Olaf’s wife or another daughter? I had to rewind the film to confirm that she’s his wife.

Good Girls Go To Paris is the second of three films that Blondell and Douglas made together within two years, the others being There’s Always a Woman (1938) and The Amazing Mr. Williams (1939). They would not appear together again for almost thirty years until MGM’s Advance to the Rear (1964). The two actors were probably initially brought together to try to capture the Nick and Nora box office magic that William Powell and Myrna Loy had generated in The Thin Man series.

Blondell and Douglas make a great comedic team & this film is by far the best of their three 1938-39 films. Blondell exudes her natural effervescence and quick tongue without any of the underlying tinge of bitterness found in many of her best roles. Her Jenny may not have gotten any breaks, but she’s not yet cynical. She is warm and loving, and any potential larceny in her heart is totally without malice.

The director and the script give Douglas a break from his frequent aggressive misogyny that he was forced to portray in many of his comedic roles (see my previous review of Two-Faced Woman (1941) where he plays opposite Greta Garbo) and that mars both of the other two Douglas-Blondell pairings. Here his Ronnie is sympathetically good natured, but too restrained to acknowledge the deep connection that he and Jenny quickly make. We’ll soon learn that he’s engaged to be married to the rich debutante, Sylvia Brand, which will be the spark that ignites the oncoming farce. And, even though Douglas is supposed to be playing an Englishman, he never attempts an accent, which I found funny in itself.

As in any well-constructed story, when things seem to be happening too fast to follow, the film slows down to allow us some introspective one-on-one moments between the characters. Jenny and the constantly agitated Olaf bond over their shared love for their simple Minnesota upbringings. Jenny works her way into Olaf’s heart by being the only one in the house not afraid to speak her mind to him. Their scene together playing cards while Olaf is in his sick bed reminded me of the gentle interaction between Deanna Durbin and Charles Laughton in It Started With Eve (1941), where Deanna's warm charm soon lifts Laughton from his proclaimed death bed.

Jenny and Ronnie also get a few, but not enough, scenes where they debate Jenny's plans to get to Paris. Their unacknowledged love grows as they gently spar back and forth. If Ronnie will just say the word, she’ll give up her plans to go to Paris, at least by herself;

Ronnie: Jenny, have you lost your flutter?

Jenny: Oh, no. I'm fluttering something

awful right now.

Ronnie, just kiss the girl already!

The chemistry between the two leads is unforced and enjoyable to bath in. Although Jenny is supposed to be younger than Blondell’s real age at the time the film was made (she was 32, Douglas was 38), there does not seem to be the usual awkward age gap between the female and males leads that was so common in films of the era, where men in their 40’s are always engaged to 17 year old girls. Such was the time.

As usual, I enjoy digging into the background of the supporting characters.

Next to Blondell and Douglas, Walter Connolly (playing Olaf Brand) is the biggest presence in the film, both physically and vocally – this big man is always shouting. You’ll recognize him as the father of Claudette Colbert’s character in It Happened One Night (1934) and as Frederic March’s hot-headed editor in the classic screwball, Nothing Sacred (1937). Connolly’s specialty was playing sweating, yelling, always outraged men who could not get the people around him to do what he wanted. Although a memorable character (your enjoyment of his screen persona may vary), his main career in Hollywood was short (1932 to 1940) after which he died at age 53.

Alan Curtis (playing Tom Brand) was a handsome actor who often got close to leading and supporting roles from the late ‘30’s until his death (following surgery) in 1953. Some of his more notable parts were as Babe Kozak, the hot-headed and inexperienced robber opposite Bogart and Ida Lupino in High Sierra (1941) and the engineer whose loyal secretary (Ella Raines) needs to find The Phantom Lady (1944) to save him from execution.

Dorothy Comingore plays an uncredited tearoom hostess.

Can you pick her out in the lineup of cute waitresses that introduces us to

Blondell’s character? In two years time she would be acclaimed for playing the

feather-brained second wife of Charles Foster Kane in Orson Welles Citizen Kane

(1941). But her star quickly fell as she felt the wrath of William Randolph

Hearst who hated his inferred portrayal in the film and Comingore’s character

who was modeled after his mistress, Marion Davies. Hearst used his power to

destroy Dorothy’s career. Her fate was sealed when she was blacklisted for

refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee. She spent

time in an asylum, became an alcoholic and died at age 58. [I think that's her third from the right standing next to Blondell]

Although Isabel Jeans (playing Caroline Brand) did not make much of an impression for me in this film, she soon had a much better role playing Mrs. Newsham in Alfred Hitchcock’s’ Suspicion (1941). Sauvé Alexander D'Arcy (playing Paul Kingston), went on to star in the underground cult classic, Horrors of Spider Island (1960).

And finally, a tip of the hat to hard working actor Sam McDaniel as the confused train porter trying to figure out where to put Jenny up for the night. You’ve seen him in at least one of his over 200 roles, almost all uncredited and almost all playing porters, janitors or servants.

Good Girls Go To Paris is from a story by Oscar nominated

Lenore J. Coffee (Four Daughters, 1938) and William J. Cowe (Kongo, 1932

[Director]), with a screenplay by Oscar nominated Gladys Leham (Two Girls and a

Sailor, 1944) and Ken Englund (No, No, Nanette, 1940). The script is

well-written and generates a lot of fun scenes for Blondell to show off her

innate comedic chops. Straight man Douglas manages to get in a few zingers as well, but his character is more reactive than proactive in driving the storyline.

The direction by Alexander Hall (Here Comes Mr. Jordan, 1941) is fast-paced and keeps the 75 minute story in constant motion. One does tend to lose track of the convoluted complications that come up between Jenny and almost everyone in the Brand household, but – as in the best films of this sort – we’re having too much fun to be concerned with trying to keep the plot straight. Has anyone ever figured out who killed Sean Regan in The Big Sleep (1946)?

Is GOOD GIRLS GO TO PARIS worth my time? A definite yes. If you like 1930’s romantic comedy’s this is a probably a little gem that you’ve overlooked. A nod as well to cinematographer Henry Freulich for his assured hand on the camera and his unfussy, but well-chosen, set ups that never distract us from story. He specialized in light fare and B comedies, being Director of Photography on many of the Blondie films from the 30’s to the 50’s. The only complaint I might have is that the film is TOO short at 75 minutes. I would have enjoyed being with Blondell’s Jenny for another half hour.

Availability: As far as I can determine, the film has never had an official DVD release, which is a shame. It is available as a print-on-demand DVD from the usual grey market sources, and watchable copies are currently up on the interweb. Keep your eyes open for it to turn up on TCM.

.jpg)

.jpg)