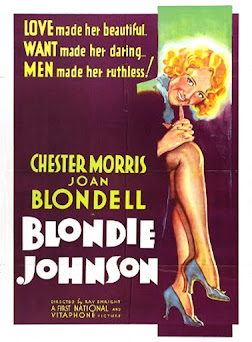

LOVE made her beautiful… WANT made her daring… MEN made her ruthless!

Joan Blondell steps into her first big lead role for this Warner Bros Pre-Code gangster film with a twist. For the first time, it’s the rags to riches story of a female criminal, but she gets there by using her brains and not her body – and without any machismo strong arm tactics.

Victoria ‘Blondie’ Johnson’s backstory is told in a quick secession of powerful opening scenes that lets Blondell show off her considerable, although frequently underused, dramatic acting chops. At the end of her rope like so many others during the Depression, a disheveled Blondie is denied government assistance after she loses her job for not giving in to the advances of her boss. Her sick mother dies, following on the heels of the death of Blondie’s younger sister (from an implied, but unstated illegal abortion) who had ‘got into trouble'. Lectured not to lose hope by a well meaning, but clueless priest, Blondie now knows how to take on the world;

“I know what it's all about. I found out the only thing worthwhile is dough! And I'm gonna get it, see!

Scraping together enough money to buy a snappy looking

dress, but otherwise broke, Blondie has one thing going for her – brains.

She’s quick enough to figure out the best angle for whatever it’ll take to move

her ahead. Hitting town, she teams up with her taxi driver (Sterling Holloway, above)

to run a small scale sob story scam fleecing dough out of men dopey enough to

give her taxi fare, plus a bit extra for the sake of her big puppy dog eyes.

His leads to her meeting Danny Doyle (Chester Morris), the not-too-bright, but

handsome, right hand man to mob boss, Max (Arthur Vinton), who is running this

part of town.

Blondie sees Danny as her next step up the ladder and so enters into a business partnership with him to advance his career – with her pulling the strings. Blondie and Danny are also clearly hot for each other, but Blondie won’t give in to sentiment until she’s acquired her goal of being on top.

“I got plans. Big plans! And the one thing that don't fit in with 'em is pants.”

Danny also wants a success, but he’s not smart enough to see Blondie’s end goal – all he can see is a gorgeous blonde. His inability to think with his head and not his dick will be the wedge that ultimately splits the partnership apart, with potentially deadly consequences.

Blondie starts by engineering a courtroom stunt to free Danny’s immediate boss, Louie (Allen Jenkins, above right), from an iron clade case against him. She pretends to be Louise’s pregnant bride-to-be, and swings the jury to a Not Guilty decision with a funny, over the top performance. Everyone is happy except Max, who had intended for Louie to take a fall to get the heat off his back. When Max plans to retaliate against Danny, Blondie steps in to smoothly take control of his gang and engineers to have Max rubbed out.

Blondie then starts up a large front operation with Danny as titular head, but with her running the operation behind the scenes. The office is massive, employing more staff than most large newspapers. What the business is supposed to be is never clarified, but it’s related to the ‘insurance’ scam that Max had been previously running.

Danny continually pushes Blondie to give in to his

advances. Even her girlfriends wonder why she’s holding out when she clearly

loves the big palooka. When she refuses, Danny’s man-child reaction is to be a

jerk. He takes up with Max’s ex-main squeeze (Claire Dodd) and neglects the

business. Things come to a head when the gang rallies behind Blondie as she

pushes Danny out of the gang and the head office, and into the gutter.

The business is running smoothing with Blondie now the official public face until Louie gets fingered for Max’s murderer. Who sold him out? The gang is convinced that Danny squealed and demands that Blondie give the order to have him silenced. In a tense scene, we watch Blondell’s face display her conflicted emotions at giving that order. But can she go through with it?

Without giving too much away, the film ends two minutes too late on a quasi-happy note, not dissimilar to Barbara’s Stanwyck’s exit in Remember the Night (1940). The very long leash given to Blondie’s criminal activities and her refusal to defer to a man throughout the film is suddenly snapped back in what feels like a studio mandated ending designed to send the audience away in an upbeat mood. The penultimate scene between Blondie and Danny would have made for a very satisfying finale without betraying the arc of the film or its characters. Alas, such ‘happy’ endings were de rigueur for many films of the day and would certainly be the norm starting a year later when the Code began enforcing its own rules.

Blondie Johnson gives Joan Blondell what might well be her best sustained performance in any of her many films (she made an amazing 38 movies between 1930 and 1934). She gets to run the gamut of emotions while still maintaining her high quotient of quotable quips that she was noted for. Joan is believable both as both a beaten down waif and as the glamorous Queenpin of a powerful criminal organization.

Chester Morris is Blondell’s perfect match in the film. Most noted for his long run playing the title character of the Boston Blackie films in the 40’s, he is convincing as the semi-ambitious, handsome, but slightly dumb lump of clay that Blondie can mold to get what she wants. Morris isn’t required to show a very wide range of reactions, but that’s what you would expect from a guy like Danny.

The film is stuffed full of great character actors, lead by The Falcon’s (Tim Conway) sometimes right hand man, Allen Jenkins. Jerkins specialized in playing sidekicks to detectives, cops and gangsters. Even though he arranges to have his old boss rubbed out, you get the feeling that Jenkins could never do you any real harm (watch him opposite Lee Tracy in The Blessed Event, 1932, as an amusingly nonthreatening thug). Jenkins’s was born to play the comedic foil and he will always have a special place in my heart for voicing Officer Dibble on Top Cat (1962).

Also keep an eye open for Tom Kennedy, who played the poetry-reciting cop in the Torchy Blaine series and for Mae Busch who was Oliver Hardy’s long suffering wife in several Laurel and Hardy films. I recently watched her give a great performance as Lon Chaney’s girlfriend in The Unholy Three (1925). Also spotted was the quintessential pencil-necked sourpuss, Charles Lane, making a brief appearance as a cashier.

Although technically a drama, the actors deft handling of the script gives Blondie Johnson the feeling of an edgy romantic comedy, a feeling greatly enhanced by Blondell’s sharp, acerbic dialogue. Minus the gangster angle, the plot of the film parallels Baby Face (1933) that would open just four months after Blondie Johnson. Barbara Stanwyck’s character in Baby Face also maneuvers to the top of the world, but unlike Blondie, she’s explicitly gets there on her back. The much darker and richer Baby Face would be one of the last straws for the industry before the Code clamped down on ‘amoral’ female leads, shutting them up and putting them back in the kitchen where it believe they belonged.

Blondie Johnson is perhaps the definitive feminist gangster film, showing the world what a criminal organization run by a woman would be like. Although Blondie is no less ruthlessness than her male counterparts, her decisions are not ruled by testosterone. She gains the complete loyalty of her gang not through fear and intimidation, but through the good management techniques of treating them with respect and not welshing on their share of the take.

Blondie’s inner circle of confidants are two women who were with her from the beginning – Mae Busch and Toshia Mori (The Bitter Tea of General Yen, 1932)(both above). Pay attention to how they are framed whenever they appear on screen. In their almost every scene, they are interacting only with Blondie and without the presence of men, or at least putting them in the positions of on-lookers. It’s never made clear as to what their role in organization is, but they whatever they do, they clearly have clout.Blondie Johnson was directed by Ray Enright and Lucien Hubbard from a screenplay by Earl Bladwin (Doctor X, 1932; Wild Boys of The Road, 1933). Tony Gaudio, prolific cinematographer and frequent cameraman for Bette Davis, knew his way around a gangster story, having helped to establish the Warner Bros look in the 1930’s. He won an Oscar for his work on Anthony Adverse (1936), with his best-loved work probably being for the breathtaking Technicolor cinematography of The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938).

Is Blondie Johnson Worth My Time? A two-thumbs up, yes. Almost everything works in this 67 minute film that is a showcase for Joan Blondell's huge talent. It’s relatively light touch also makes it the perfect 1930’s Warner Bros gangster film for people who don’t like 1930’s gangster films.

Availability: Warner Archive released Blondie Johnson a few years ago on DVD. It’s also currently playing on a variety of streaming services.

.jpg)

.jpg)